In the fight against C. diff, Grief is Our Superpower

Other Categories

“everything I ever did

was just another way to scream your name

over and over and over and over again”

Florence Welch, South London Forever

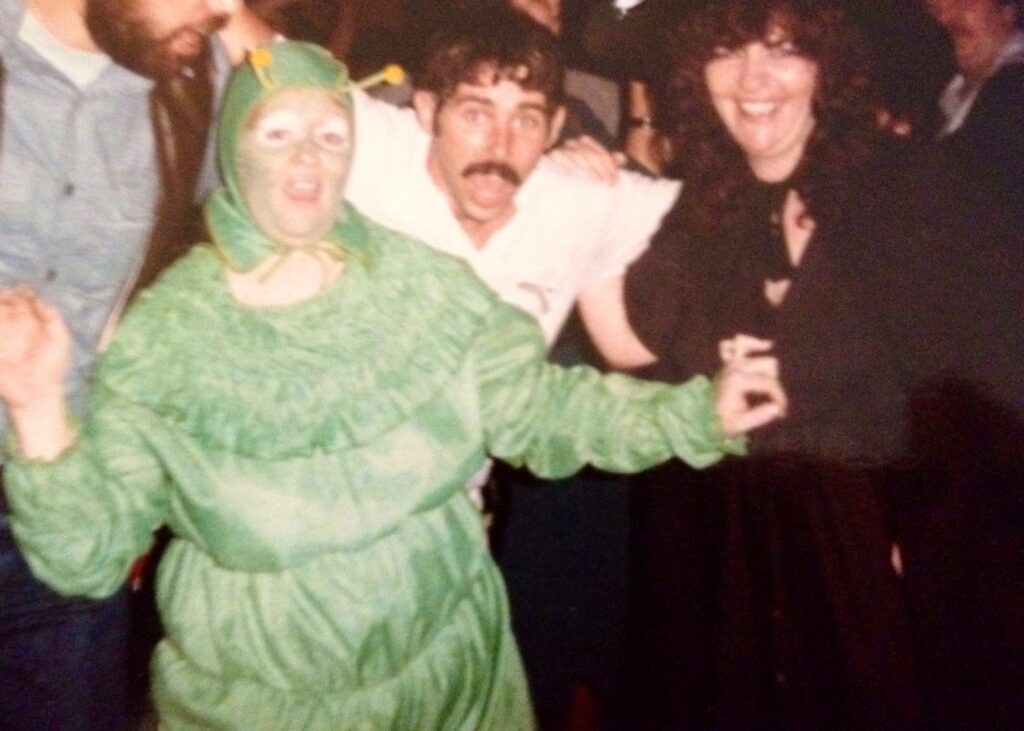

My mother, Peggy, loved Halloween. She also loved Dia de los Muertos, which she taught to her kindergarten class. It served as an early conversation about mourning while teaching her students, many of whom were from South Asia and the Caribeann, about the Mexican holiday. As far back as I can remember, Mom emphasized the importance of grief and mourning. Despite being a poor, single mother, she made sure that she, and when we were old enough to attend funerals, Liam and I were well-dressed.

When her brother Gerard died unexpectedly in June 1994, neither Liam (17) nor I (20) had appropriate clothes, having outgrown our adolescent suits, and Mom had lost weight. She took us all to Macy’s and outfitted us properly. This was, on the one hand, a sign of respect for her brother, whom she loved very much. On the other hand, it was armor. Now 40, Mom had been a single parent for 15 years, working and putting herself and now me through college. She worked six days a week (Sunday through Friday) and often studied on Saturdays. Mom had fashioned a tough, stoic public face for difficult times. But, because she loved deeply and with abandon, the facade wasn’t very thick. The facade could be maintained for the wake and funeral, so long as no one she was close to empathized too directly. “Don’t be nice to me,” she’d say through a gritted smile, when a sibling or close friend’s sympathy threatened her public face. But privately, Mom unleashed her emotions, sobbing, crying, and even wailing from the pain of losing her brother and, later, her father.

Our mother was raised Catholic. She maintained some of those traditions in her life. But at her core, Mom believed and acted on our shared humanity. Mom believed in marking our loved ones’ deaths, caring for those left behind, and keeping their memories alive. Her brother, Gerard, was gay. After he died, Mom spent the next few years attending the New York City Pride Parade with his picture. She wanted him to count still. For the rest of her life, Mom was often the person who acknowledged our lost loved ones during holidays, family ceremonies like weddings and baptisms, and on their birthdays. I believe that’s why Dia de los Muertos resonated so powerfully with her. For Mom, grief and mourning did not have a specific set of stages or an endpoint at which the death of a loved one would be normalized.

My mother taught me how to mourn: public composure, private devastation, and an enduring grief for those I loved deeply, most of all her.

My refusal to “get over it” or “move on” from her death makes many people uncomfortable. I’ve definitely lost relationships due to my stubborn mourning. But grief is not just pain or absence; appropriately channeled, it can and has changed the world. When we refuse a false “closure”, our personal and, more importantly, collective grief can be our superpower.

That’s why for this year’s “See C. diff” campaign, we’re focusing on those we have lost and continue to lose to this infection. As Cody Delistraty noted in his New Yorker essay, “It’s Mourning in America,” “death is largely banished from the visual landscape” of America. Only 30 percent of Americans now die at home, with the majority dying in a hospital or care home. The last in-home wake in our family was my great-grandmother, Nana Daly, when I was a few months old. This privatization of grief and mourning leaves little evidence of the person and what their loss represents to those left behind. Though we lose three Americans to a C. diff infection every hour, the tragedy of these often preventable deaths is hidden. Public reporting is uneven and likely undercounts both infections and deaths. It doesn’t account for long-term suffering and grief that accompany months or years of recurrent C. diff infections. But we can.

The writer and AIDS activist Paul Monette wrote, “Grief is a sword, or it is nothing.” Monette ultimately lost his life to AIDS. But thanks to him and many others, we have a deep cultural knowledge of the initial AIDS epidemic. The ferocity and public mourning so prevalent in demonstrations by ACT UP and other AIDS groups fundamentally changed our healthcare system. We continue to benefit from their advocacy decades after most of them have died.

Grief is transformative. Channeled properly, grief can and has changed the world. That’s why so many of our political and cultural norms try to repress it.

For example, when the United States entered World War I, the suffragist movement marched against our involvement. They paraded through Manhattan in traditional mourning clothes in a show of solidarity with the women and children who would be widowed and orphaned due to the War. However, President Wilson, who had previously been an isolationist, struck a deal with the suffragists to support the 20th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, in exchange for their shifting their public stance from opposition to displays of patriotism. This, coupled with the sheer number of military deaths during the First and Second World Wars, began to erode public mourning.

Without a way to express it, grief can become bitterness and nihilism. It can corrode what is gentle in us until we no longer see each other as human. But when we process and respect grief, it can be channeled toward self and community healing. Grief can pierce through propaganda that pits doctors against patients, white people against people of color, Gen Z against Boomers, or straight people against queer people. When we let it, grief can bring a family together; it can build enormous and enduring solidarity. It can unite a nation.

But for grief to transform us, we have to feel it. Not just for our loved ones, but for strangers, communities we’re not a part of, people with different politics, and those in countries we’ve never visited. So this C. diff Awareness Month, we’re going to be grieving in public, for the 30,000 we’ll lose this year, for the hundreds of thousands we’ve lost over the years, and for those of us who survived C. diff, for ourselves.

In addition to being Dia de los Muertos, today is also the Gaelic holiday of Samhain. Irish and other Celtic cultures have celebrated Samhain since at least the 9th Century. While recognizing the end of the Harvest season, Irish mythology also notes Samhain as a time when the ‘doorways’ to the Otherworld opened, allowing the souls of the dead to come into our world; essentially a festival for the dead. Mom’s birthday is October 29. I feel her presence starting in mid-October and through the holiday season. Perhaps because the barriers between this world and where her soul resides are lowered, or because it’s a time spent with family and friends, often filled with remembrance and reflection. Either way, I welcome feeling closer to her, and other loved ones I’ve lost. So I lean into it.

Some losses are too big to “get over.” Grief is transformative when we resist fake “closure.” Grief is powerful when we stop trying to suppress it and befriend it. Grief can be acute and it can be lifelong. So this year, let’s be loud about our grief; let’s honor those we’ve lost by telling their stories, remembering their lives, and upholding their values. Let’s embrace this as a time to be in community with our dead and, as importantly, with each other.

Leave a Reply