Guest Blog: Fecal Microbial

Other Categories

This post was written by Gary H. Hoffman, MD, a colon and rectal surgeon with more than 35 years of experience in Beverly Hills, CA. Dr. Hoffman is the Clinical Chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery at Cedars Sinai Medical Center and the Clinical Chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery. He has written extensively about Clostridium difficile, FMT, and their treatment options. Dr. Hoffman is board certified, you can learn more about him at lacolon.com.

This post was written by Gary H. Hoffman, MD, a colon and rectal surgeon with more than 35 years of experience in Beverly Hills, CA. Dr. Hoffman is the Clinical Chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery at Cedars Sinai Medical Center and the Clinical Chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery. He has written extensively about Clostridium difficile, FMT, and their treatment options. Dr. Hoffman is board certified, you can learn more about him at lacolon.com.

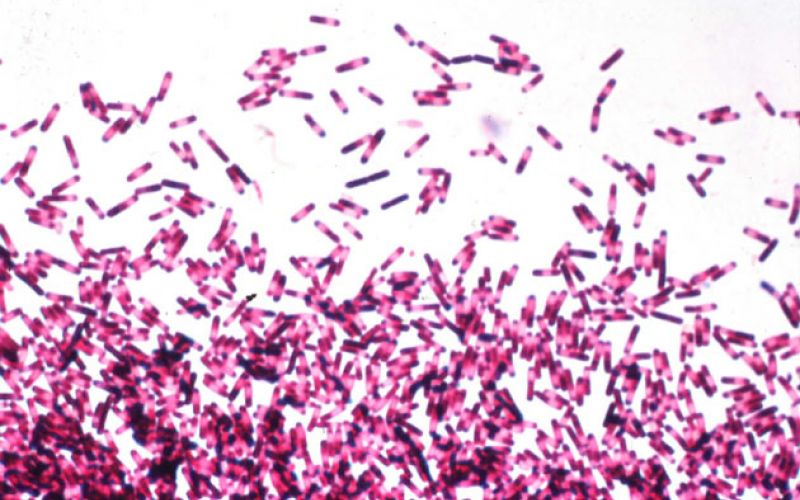

When antibiotics and other first-line treatments fail to stop a Clostridium difficile infection, you have two options: continue to let the infection keep you from having the quality of life you want, or consider a new — and somewhat unconventional — treatment.

C. difficile is notoriously difficult to treat. Even with a full course of antibiotics, between 20 and 30 percent of patients experience a recurrence. However, studies show that fecal microbial transplantation, often known simply as FMT, can cure between 80 and 90 percent of C. difficile infections with just a single treatment.

In the digestive tracts of healthy people, the good bacteria can fight off the nefarious strains and keep the gut in proper working order. When a patient takes antibiotics however, these drugs often kill off too much of this good bacteria. This allows strains such as C. difficile to take over. FMT takes fecal matter from a healthy donor and introduces it into the colon of the patient, replenishing the good bacteria that have been lost.

Finding a Donor for FMT

Unlike with blood, bone marrow or other similar donations, there is no reason to require a donor with genetic similarities or a matching blood type for fecal microbial transplantation. However, many patients still use fecal matter from an immediate family member or other close relative.

This is most likely simply because it is easiest to discuss the procedure and identify a willing donor with those closest to you. This treatment — while effective — is still not something most people want to discuss with co-workers or others who require polite company. Donors are often children, spouses, siblings or parents. The treatment poses no risk to the donor, and little risk to the recipient.

Donors must meet stringent criteria. To identify a good candidate, consider only potential donors who:

- Have not recently needed antibiotics for an infection

- Suffered from any condition that compromised their immune system

- Do not suffer from any type of gastrointestinal disorder

- Have not traveled to places where endemic diseases are common

- Have not gotten a tattoo or piercing in at least six months

- Do not have a history of drug use or high-risk sexual behavior

- Have not had a C. Diff infection in the past

Even if your potential donor meets all of these qualifications, they will need to also undergo a series of tests to ensure the health of their gut bacteria. Because of these high standards, only a small percentage of those who are identified as potential donors are approved to donate.

If you cannot find a friend or family member to serve as a donor, you do have one other option. Because of increasing demand for donations for FMT, there are a few stool banks that offer pre-screened donor stool for patients who need it.

Donor Testing and Approval

Despite hundreds of trials and thousands of patients who have undergone FMT, there has been no known transmission of infection. This is due to the stringent testing procedures required for donation. Any potential donor must supply both a blood sample and a stool sample, which are used to conduct a comprehensive series of tests to ensure there is no exposure to infectious pathogens.

These panels look for a number of problematic bacteria and other problems. This includes testing for:

- Hepatitis (A, B & C)

- HIV/AIDS

- Syphilis (RPR)

- Ova and parasites (O & P)

- C. difficile

- Giardia

- Other culture and sensitivity testing as necessary

Many times, these tests rule out potential donors even if they show no symptoms. It is not uncommon for the tests to identify an asymptomatic rotavirus or other minor infection that prevents patients from donating. This is why it is not uncommon for patients to identify and test several potential donors.

Preparing for the Procedure

Once the stool sample, collected during a normal bowel movement, is ready, it is mixed with a saline solution and introduced into your colon during a colonoscopy. In order to prepare for this procedure, you must:

- Follow your doctor’s orders about any medications

- Drink only clear liquids the day before the procedure

- Drink a laxative preparation, as prescribed by the doctor

- Do not eat or drink anything after midnight the night before the procedure

Colonoscopies are typically done under twilight anesthesia, meaning you will be awake but will not remember the procedure. During the colonoscopy, the doctor will insert the small, flexible tube into your rectum and advance it as far as possible. As the tube is slowly removed, it will dispense the donor sample along the entire length of your colon.

Once this process is finished, you will be taken to a recovery room until you become fully alert. It is important to have a family member or friend on hand to drive you home.

Looking Toward the Future

Many patients experience an improvement in their quality of life immediately following FMT, often reporting that they no longer suffer from diarrhea. However, it takes up to four months for the flora to fully diversify, meaning that it could take several weeks before you see a marked improvement.

Currently, the Food and Drug Administration is exercising enforcement discretion, allowing FMT to be used in fighting C. difficile infections that do not respond to conventional treatments. However, studies are ongoing to determine if the procedure can help those with a number of clinical indications, including refractory Crohn’s disease, colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and other GI disorders.

Sources:

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844905

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26070003

http://www.openbiome.org/about-fmt/

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0081330

This post fails to mention that you don’t need to find a donor anymore. There is a non-profit that will provide the fecal matter, at cost, to any hospital. Open Biome works with several providers in the LA area. Their website is cited above in a footnote, but the doctor fails to discuss it, which is a serious omission because lack of donors is holding back many folks who have C Diff from getting a much more reliable, less costly, and less invasive cure.

Hi Julia,

Thanks for your comment. We have OpenBiome listed as a source for FMT under our Patient Resources page. I’m not sure if Dr. Hoffman uses OpenBiome, as some practitioners still use known donors or stool banks in their health facilities.

OpenBiome has developed a pill containing bacteria from healthy donors. You do not even need to do FMT surgically anymore. You just swallow about 40 or 50 pills in one sitting and perhaps repeat on other days.

Is that effective tho?